There’s so much wrong with her civil complaint (see below)… but for now, let’s focus on this:

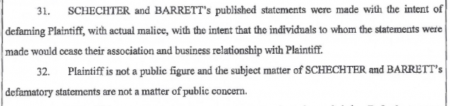

She’s appeared in hundreds of porn scenes, been interviewed by Howard Stern, authored multiple books, owned one of the largest adult talent agencies of its day (ATMLA), and charged $395 a head at seminars and speaking engagements — but Shy Love now claims in court documents that she’s not a public figure.

This is the same Shy Love who has been one of the most outspoken and confrontational people in the adult business. Remember that time when she helped spearhead a revolt at LATATA?

Shy appeared on The Howard Stern Show on May 11, 2006 and rode the Sybian. Report courtesy of MarksFriggin.com

Howard had porn star Shy Love come in. Howard wondered why there are so many porn ”stars” out there that he’s never heard of. Shy said that she’s done 700 movies so she’s been in a lot. She told Howard that she once did something similar to the clip that they played earlier. She said that she wasn’t able to slurp the stuff like the woman was doing. That’s not her thing and she’s not even able to swallow. She said she does other things like anal and she loves that. She said that she’s had great orgasms doing that and they’re much better than vaginal orgasms.

Howard read a comment from Shy about how she turned down Playboy because they didn’t offer her enough money. Howard said he didn’t believe that. She said that she still does stuff for Playboy but she didn’t do the centerfold thing. She said that she would have been paid about $25,000 to be a centerfold and she wouldn’t be able to do anything in the adult industry for up to four years. She said she could make that kind of money in a month in the industry so she turned it down.

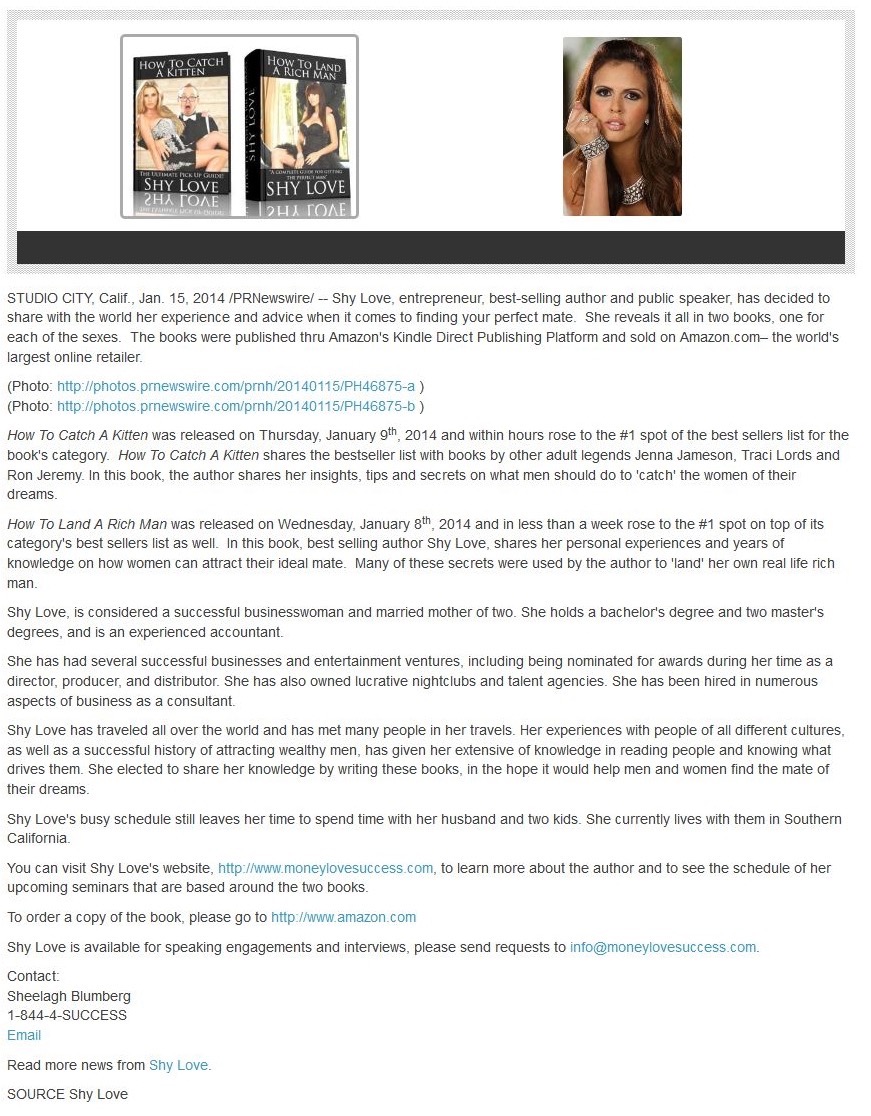

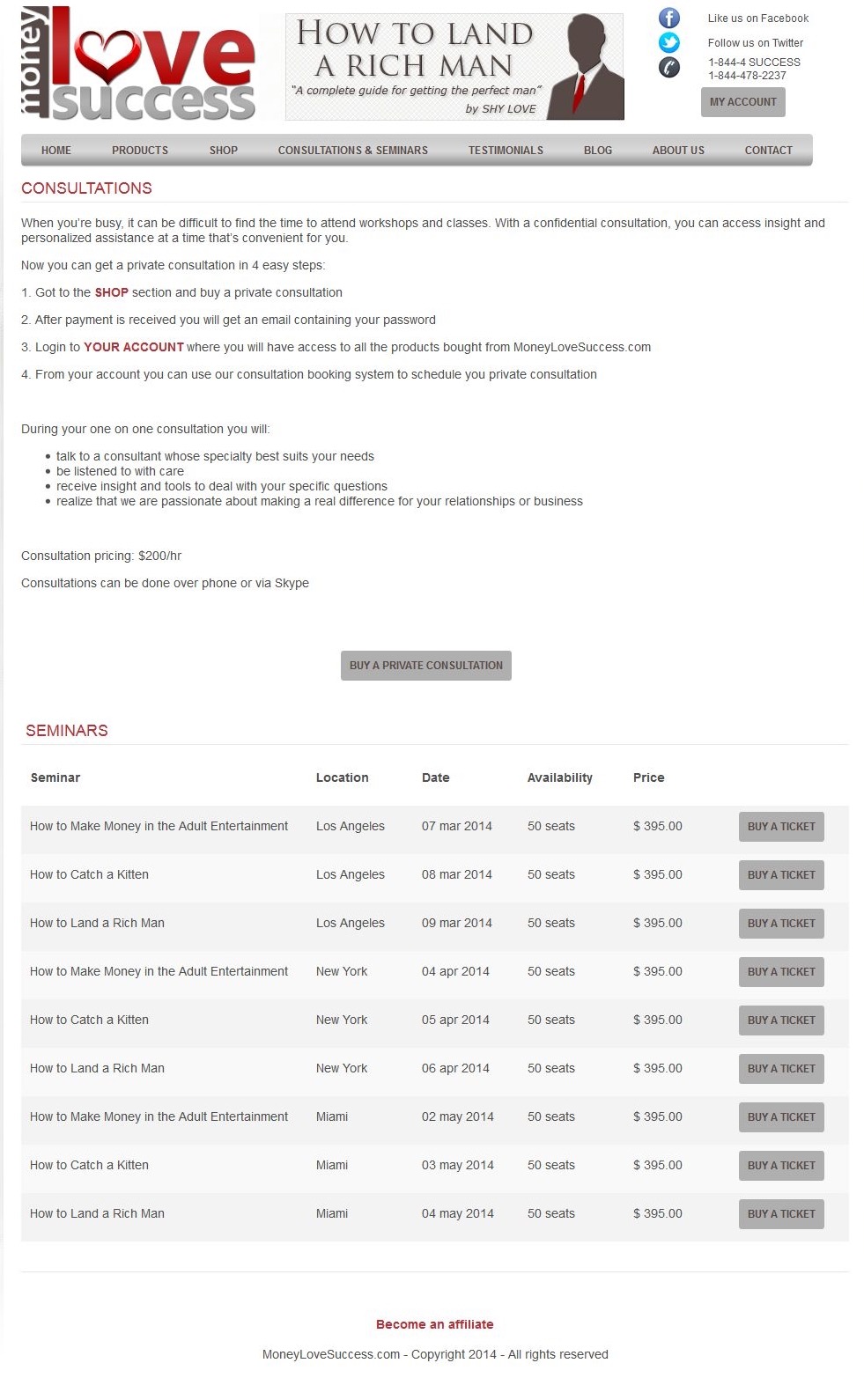

Author and Public Speaker

Shy has authored three books, two of which are offered for sale on Amazon.com.

How To Make Money In Adult Entertainment (Her own website)

A whole YouTube account full of videos for Money Love Success

AVN 2014 video of a seminar for her book How To Catch A Kitten

Shy’s PR from January 2014 about her two new books and hyping her seminars in a link to her site.

Interview with Shy from July

Her author page at Amazon.

She gives seminars in LA, NY, and Miami for $395 per person. Phone or Skype consultations for $200 a pop also. http://moneylovesuccess.com/

And finally, a few words on defamation

What Defenses Are Available To People Accused of Defamation?

The most important defense to an action for defamation is “truth”, which is an absolute defense to an action for defamation.

Another defense to defamation actions is “privilege”. For example, statements made by witnesses in court, arguments made in court by lawyers, statements by legislators on the floor of the legislature, or by judges while sitting on the bench, are ordinarily privileged, and cannot support a cause of action for defamation, no matter how false or outrageous.

A defense recognized in most jurisdictions is “opinion”. If the person makes a statement of opinion as opposed to fact, the statement may not support a cause of action for defamation. Whether a statement is viewed as an expression of fact or opinion can depend upon context – that is, whether or not the person making the statement would be perceived by the community as being in a position to know whether or not it is true. If your employer calls you a pathological liar, it is far less likely to be regarded as opinion than if such a statement is made by somebody you just met. Some jurisdictions have eliminated the distinction between fact and opinion, and instead hold that any statement that suggests a factual basis can support a cause of action for defamation.

A defense similar to opinion is “fair comment on a matter of public interest”. If the mayor of a town is involved in a corruption scandal, expressing the opinion that you believe the allegations are true is not likely to support a cause of action for defamation.

A defendant may also attempt to illustrate that the plaintiff had a poor reputation in the community, in order to diminish any claim for damages resulting from the defamatory statements.

A defendant who transmitted a message without awareness of its content may raise the defense of “innocent dissemination”. For example, the post office is not liable for delivering a letter which has defamatory content, as it is not aware of the contents of the letter.

An uncommon defense is that the plaintiff consented to the dissemination of the statement.

Public Figures

Under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, as set forth by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1964 Case, New York Times v Sullivan, where a public figure attempts to bring an action for defamation, the public figure must prove an additional element: That the statement was made with “actual malice”. In translation, that means that the person making the statement knew the statement to be false, or issued the statement with reckless disregard as to its truth. For example, Ariel Sharon sued Time Magazine over allegations of his conduct relating to the massacres at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. Although the jury concluded that the Time story included false allegations, they found that Time had not acted with “actual malice” and did not award any damages.

The concept of the “public figure” is broader than celebrities and politicians. A person can become an “involuntary public figure” as the result of publicity, even though that person did not want or invite the public attention. For example, people accused of high profile crimes may be unable to pursue actions for defamation even after their innocence is established, on the basis that the notoriety associated with the case and the accusations against them turned them into involuntary public figures.

A person can also become a “limited public figure” by engaging in actions which generate publicity within a narrow area of interest. For example, a woman named Terry Rakolta was offended by the Fox Television show, Married With Children, and wrote letters to the show’s advertisers to try to get them to stop their support for the show. As a result of her actions, Ms. Rakolta became the target of jokes in a wide variety of settings. As these jokes remained within the confines of her public conduct, typically making fun of her as being prudish or censorious, they were protected by Ms. Rakolta’s status as a “limited public figure”.

California Elements of Defamation

Defamation, which consists of both libel and slander, is defined by case law and statute in California. See Cal. Civ. Code §§ 44, 45a, and 46.

The elements of a defamation claim are:

- publication of a statement of fact

- that is false,*

- unprivileged,

- has a natural tendency to injure or which causes “special damage,” and

- the defendant’s fault in publishing the statement amounted to at least negligence.

Publication, which may be written or oral, means communication to a third person who understands the defamatory meaning of the statement and its application to the person to whom reference is made. Publication need not be to the “public” at large; communication to a single individual other than the plaintiff is sufficient. Republishing a defamatory statement made by another is generally not protected.

*As a matter of law, in cases involving public figures or matters of public concern, the burden is on the plaintiff to prove falsity in a defamation action. Nizam-Aldine v. City of Oakland, 47 Cal. App. 4th 364 (Cal. Ct. App. 1996). In cases involving matters of purely private concern, the burden of proving truth is on the defendant. Smith v. Maldonado, 72 Cal.App.4th 637, 646 & n.5 (Cal. Ct. App. 1999). A reader further points out that, even when the burden is technically on the plaintiff to prove falsity, the plaintiff can easily shift the burden to the defendant simply by testifying that the statements at issue are false.

Defamation Per Se

A plaintiff need not show special damages (e.g., damages to the plaintiff’s property, business, trade, profession or occupation, including expenditures that resulted from the defamation) if the statement is defamation per se. A statement is defamation per se if it defames the plaintiff on its face, that is, without the need for extrinsic evidence to explain the statement’s defamatory nature. See Cal. Civ. Code § 45a; Yow v. National Enquirer, Inc. 550 F.Supp.2d 1179, 1183 (E.D. Cal. 2008).

For example, an allegation that the plaintiff is guilty of a crime is defamatory on its face pursuant to Cal. Civil Code § 45a. In one case, a non-profit organization (NPO) that advocates for the rights of low-income migrant workers posted flyers claiming a national retailer of women’s clothing engaged in illegal business practices by contracting with manufacturers that did not pay minimum wage or overtime. The retailer brought a defamation suit against the NPO. Although the statements would have qualified as defamation per se, the court concluded the retailer failed to establish the statements in the flyers were false, and therefore the statements could not be considered defamatory. See Fashion 21 v. Coal. for Humane Immigrant Rights of L.A., 12 Cal.Rptr.3d 493 (Cal. Ct. App. 2004).

Public Officials

In California, public officials are those who have, or appear to the to have, substantial responsibility for or control over the conduct of government affairs. For example, the following persons have been considered public officials in California:

- A police officer, an assistant public defender, an assistant district attorney, and a government employed social worker.

Public Figures

In California, to classify a person as a public figure, the person must have achieved such pervasive fame or notoriety that he becomes a public figure for all purposes and in all contexts. Someone who voluntarily seeks to influence resolution of public issues may also be considered a public figure in California. For example, the following persons have been considered public figures in California:

- A former City Attorney who also represented the city’s redevelopment agency;

- A licensed clinical psychologist whose so-called “Nude Marathon” in group therapy is a means of helping people to shed their psychological inhibitions by the removal of their clothes;

- An author and television personality;

- The founder of a Church that has a program for the rehabilitation of drug addicts;

- An associate of Howard Hughes, a famous aviator, movie producer, and billionaire, from approximately 1956 to 1970 who functioned as an “alter ego” and “personal representative” of Mr. Hughes;

- A real-estate developer who was interested in building a housing development near a toxic chemical plant; and

- A “prominent and outspoken feminist author” and anti-pornography advocate.

Limited-Purpose Public Figures

A limited-purpose public figure is a person who voluntarily injects herself or is drawn into a particular public controversy. It is not necessary to show that she actually achieves prominence in public debate; her attempts to thrust herself in front of the public is sufficient. Copp v. Paxton, 52 Cal.Rptr.2d 831, 844 (Cal. Ct. App. 1996). As with all limited-purpose public figures, the alleged defamation must be relevant to the plaintiff’s voluntary participation in the public controversy (if the issue requires expertise or specialized knowledge, the plaintiff’s credentials as an expert would be relevant).

In California, the following persons have been considered limited-purpose public figures:

- The president of two corporations located in a California village that opposed the rezoning of property adjacent to his property. Kaufman v. Fidelity Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass’n, 189 Cal.Rptr. 818 (Cal. Ct. App. 1983);

- An individual who publicly claimed to be an expert in earthquake safety and a veteran in earthquake rescue operations. Copp v. Paxton, 52 Cal.Rptr.2d 831 (Cal. Ct. App. 1996).

Actual Malice and Negligence

In California, a private figure plaintiff bringing a defamation lawsuit must prove that the defendant was at least negligent with respect to the truth or falsity of the allegedly defamatory statements. Public officials, all-purpose public figures, and limited-purpose public figures must prove that the defendant acted with actual malice, i.e., knowing that the statements were false or recklessly disregarding their falsity. See the general page on actual malice and negligence for details on the standards and terminology mentioned in this subsection.

Privileges and Defenses

California courts recognize a number of privileges and defenses in the context of defamation actions, including the fair report privilege, the opinion and fair comment privileges, and substantial truth.

There also is an important provision under section 230 of the Communications Decency Act that may protect you if a third party – not you or your employee or someone acting under your direction – posts something on your blog or website that is defamatory. We cover this protection in more detail in the section on Publishing the Statements and Content of Others.

Neutral Reportage Privilege

The California Supreme Court has not formally recognized the neutral reportage privilege. Nevertheless, several federal courts have applied the neutral report privilege in cases involved California law and there are relatively strong indications that state courts in California would apply the privilege if faced with the proper fact pattern.

The California Supreme Court indicated a possible willingness to consider the neutral report privilege in the context of public figure defamation. In that case, which involved an allegation that the plaintiff, a private citizen, participated in the Robert Kennedy assassination when he was 21 years old, the California Supreme Court held that the neutral report privilege did not apply to cases where the plaintiff was a private figure. Khawar v. Globe International, 19 Cal. 4th 254, 271 (Cal. 1998). The court left open the question, however, whether the neutral report privilege would apply if the defamatory statement involved a public figure.

In addition, several lower California courts have expressed support for the privilege without directly ruling that the privilege applies. See Weingarten v. Block, 102 Cal. App. 3d 129, 148 (1980); Grillo v. Smith, 144 Cal. App. 3d 868, 872 (1983); Stockton Newspapers, Inc. v. Superior Court, 206 Cal. App. 3d 966, 981 (1988); Brown v. Kelly Broad. Co., 48 Cal. 3d 711, 732-33 n.18 (Cal. Ct. App. 1989).

Although their application of the privilege is not binding on California state courts, two federal courts in the state have applied the neutral reportage privilege in situations involving the following:

- A college basketball player (ruled a public figure) who accused his coach (also deemed a public figure) of participating in payments made to the player by team boosters. Barry v. Time, Inc., 584 F. Supp. 1110, 1112 (D. Cal. 1984). The court held that there was no requirement that the person making the accusation have a reputation for “trustworthiness” for the neutral report privilege to apply.

- The details published by a tabloid, News of the World, about the private life of a well known actor. Ward v. News Group Int’l, 733 F. Supp. 83 (D. Cal. 1990). The court emphasized that the republication occurred in a fair and accurate manner and that the tabloid published the actor’s denial along with the accusation.

Statute of Limitations for Defamation

California’s statute of limitations for defamation is one (1) year. See California Code of Civil Procedure 340(c).

California applies the single publication rule pursuant to California Civil Code 3425.1-3425.5. A California Court of Appeals recognized the single publication rule in the context of publications on the Internet. Traditional Cat Ass’n, Inc. v. Gilbreath, 13 Cal.Rptr.3d 353, 358 (Cal. Ct. App. 2004). For a definition of the “single publication rule,” see the Statute of Limitations for Defamation section of this guide.

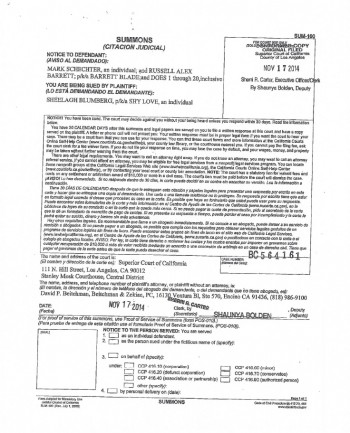

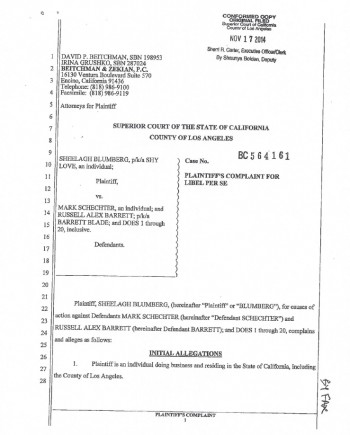

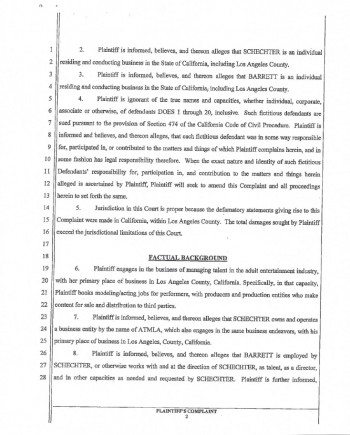

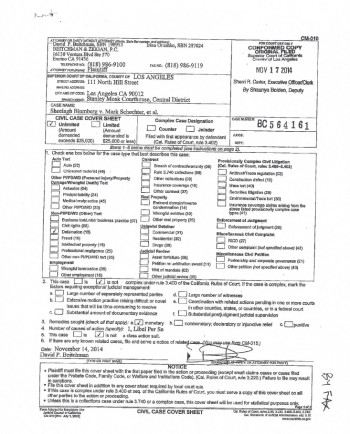

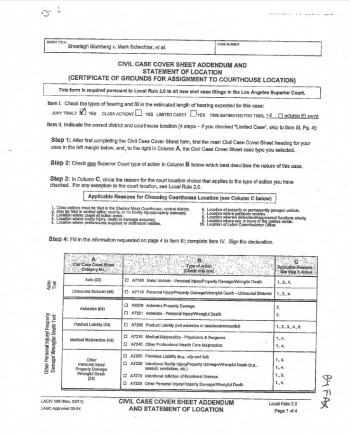

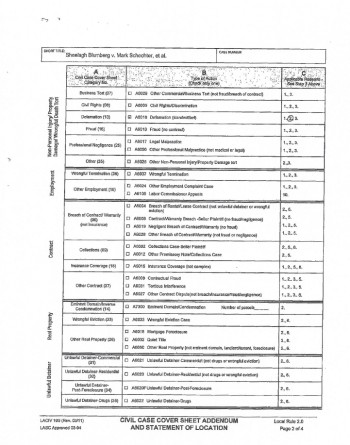

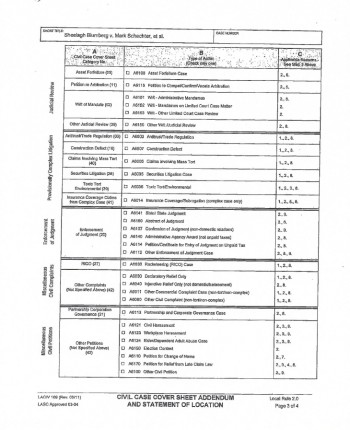

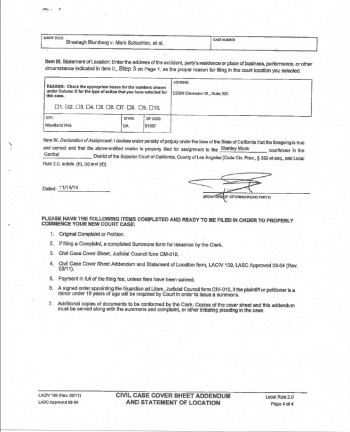

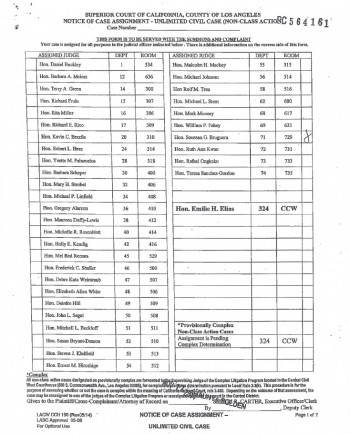

Shy Love’s (poorly drafted) complaint, filed November 17, 2014:

Shy Love declined to comment on this story.

[…] Howard had porn star Shy Love come in. Howard wondered why there are …read more […]

[…] Howard read a comment from Shy about …read more […]

Poor Shy. As long as she has some oats, alfalfa and her foals, she’ll never be bankrupt.

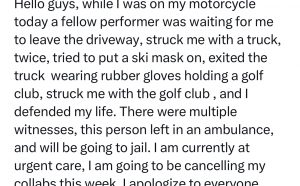

[…] Nov 17, ex-adult performer turned talent agent Shy Love (aka Sheelagh P Albino Blumberg) filed suit against agency owner Mark Schechter and director Barrett Blade, claiming in part that they had […]

[…] couple of weeks back, adult performer turned talent agent Shy Love filed a lawsuit against Mark Schechter, the guy who purchased her old […]

[…] November, ex-adult performer turned talent agent Shy Love (nee Sheelagh Blumberg) sued Mark Schechter, the man who now owns her old agency, ATMLA, for defamation. As TRPWL has indicated in its […]

[…] Were you not the one who started the press leaking thing?? I know what your thinking, The blogger that put the suit up got his info from “google […]

[…] attempt to oust Schechter’s agency, ATMLA, from LATATA in 2014. Then, last November, Shy Love sued Schechter for defamation. Schechter countersued the following […]