She is the celebrity face of the global fight against sex slavery, but now some are asking if Cambodia’s Somaly Mam has exaggerated victims’ stories.

Raped at 12, forced to marry at 15 and then sold into prostitution, Somaly Mam has risen from Cambodia’s brothels to be the glamorous, celebrity face of the global anti-sex slavery movement.

At a $100,000-a-seat gala fund-raising dinner at New York’s Gotham Hall last week, the beautiful and charming campaigner rubbed shoulders with Hollywood stars and some of America’s top business people, as actress AnnaLynne McCord broke down on stage while revealing her own dark days of child rape and sexual abuse.

”I was suicidal. I cut my arms up … but something, I don’t know what, led me to Somaly Mam,” she said, clutching Somaly’s hand.

The energetic head of the multimillion-dollar non-profit Somaly Mam Foundation, Mam was named among Time’s 100 most influential people and a CNN hero, after escaping a life in which she was locked up, tortured, raped and threatened with death.

Advertisement

But as Mam flew back to Cambodia from New York with a $US1 million ($1.05 million) award, the latest of many international prizes she has received, there were questions about whether she has exaggerated victims’ stories, including the alleged kidnap of her own daughter.

Some of the most sensational testimonials, including the mutilation and abuse of child prostitute Long Pros and the imprisonment of another girl, Meas Ratha, in a Cambodian brothel, have been crucial in helping Mam raise millions of dollars for her charity.

According to the story initially told by Long Pros, she was 13 in 2005 and hadn’t even had her first period when a young woman kidnapped her and sold her to a brothel in Phnom Penh.

The story she told television documentaries, international newspapers and The Oprah Winfrey Show was even more horrific than Mam’s own story, symbolising the depredation of the 21st-century version of slavery.

The brothel owner, a woman, beat and tortured her with electric current until she acquiesced, she claimed. She was kept locked up, her hands tied behind her back, except when she was with customers.

Three times she was painfully stitched up and resold as a virgin, for which brothel owners charge large sums. ”I was beaten every day, sometimes two or three times a day,” claimed Pros, who expressed her grief to US secretary of state Hillary Clinton and actresses including Meg Ryan and Susan Sarandon.

Pros said she was never paid, could not insist on condoms and twice became pregnant and was subjected to crude abortions, the second of which left her in great pain, prompting her to plead with the brothel owner to have time to recuperate.

”I was begging, hanging on to her feet and asking for rest,” Pros said. ”She got mad.” That’s when the woman gouged out Pros’ right eye with a piece of metal. When the eye became infected, spraying blood and pus on customers, the owner discarded her and she was taken in by Mam’s organisation, she said.

However, in a series of articles about Mam’s most highly publicised sex-trafficking victims, The Cambodia Daily has revealed that at least part of Pros’ story was fabricated.

Quoting medical records and Pros’ parents, the newspaper said the girl in fact had her eye removed in a hospital because of a tumour that developed in childhood.

Parents Long Hon, 60, and Sok Hang, 56, did not want Fairfax Media to come to their village in Svay Rieng province to talk about their daughter, who is working in a Somaly Mam-linked Voices for Change program run by the Sydney-based non-profit Project Futures.

Asked by telephone how his daughter, who has changed her name to Somana Long, lost her eye, Long Hon said: ”I don’t want to speak again and again about this … she had a disease and I took her to hospital myself.” Sok Hang said she also did not want to comment on her daughter in case she loses her job.

Te Sereybonn, director of the Takeo Eye Hospital, told Fairfax Media that Pros came to the hospital three times in 2005 and eye specialist and surgeon Pok Thorn told him she had a tumour inside her eye that had to be removed. ”The eye [problem] was not caused by beating,” he said.

Thorn was quoted by The Cambodia Daily as saying: ”I operate and after the operation I arrange with my administrator here to find the organisation to help her.”

Thorn was reluctant to talk about Pros to Fairfax Media, citing patient confidentiality, but said he remembered the girl. ”If you show the photo of her eye to doctors around the world they would know what happened to her, really,” he said.

There is also at least one other version of the cause of Pros’ eye loss. A book by New York-based fashion photographer Norman Jean Roy called Traffik, published in 2008, tells how Pros lost her eye after being kicked in the face by a pimp and the eye was removed in hospital after becoming infected.

Asked about the conflicting stories, Mam’s communications department in New York replied by email: ”The physical evidence, her assurances and research into her accounts led us to believe them to be true.”

In 1998, the harrowing story of Meas Ratha in a French prime time television documentary helped propel Mam into the international spotlight.

Ratha told how she had been promised a job as a waitress but ended up captive in a brothel in Phnom Penh. ”I was very young and didn’t know what to do,” she said to the camera, before crying and receiving a comforting squeeze from Mam.

But 16 years after the interview, Ratha, now 32 years old and married, has been quoted by The Cambodia Daily as saying the story was fabricated and scripted by Mam as a means of drumming up support for the organisation.

”The video that you see, everything that I put in is not my story … Somaly said that … if I want to help another woman I have to do [the interview] very well,” she was quoted as saying.

Ratha declined to speak to Fairfax Media.

”We don’t know why, nor will we speculate on why Meas Ratha has allegedly made the claims the Daily has reported,” said Mam’s communications department in reply to questions.

Last year Mam admitted a comment she had made to the UN General Assembly was inaccurate and that the Cambodian army had not killed eight girls following a raid on her organisation’s Phnom Penh centre in 2004.

”At the April United Nations General Assembly event, some of my comments were ambiguous and my intention was not to misrepresent the course of events in 2004 … I had in no way intended to allege that the girls were murdered during the shelter raid,” Mam said in a statement after police had questioned the claim.

”Rather, I had received information some time after the event via a reliable source that a number of the girls/women involved in the raid later died in a series of accidents, which we believed could have been connected to their traffickers and pimps.”

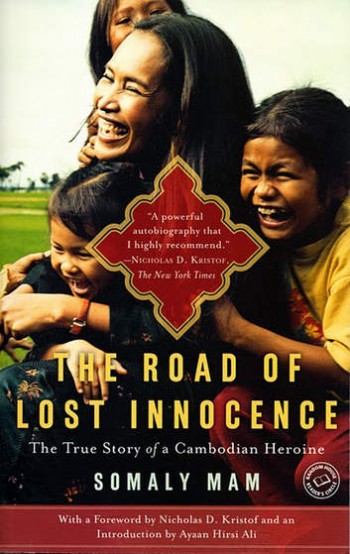

In her best-selling book The Road of Lost Innocence, which has been published in 10 languages, Mam wrote that in 2006 her then 16-year-old daughter Ning had been kidnapped by armed men and gang-raped in retaliation for her work exposing a brothel owner.

”Working closely with police and the authorities we finally tracked Ning down … she was in the hands of traffickers and along with them was a boy she knew,” she wrote.

But Pierre Legros, Mam’s former husband and Ning’s father, told Fairfax Media that Ning, who is now 23 and lives with Somaly, was not kidnapped but ran away with her then boyfriend.

Cambodia’s police said there was no reported kidnapping.

Legros said Mam, from whom he separated in 2004, sees herself as a victim and by including their daughter also as a victim she ”becomes a pure victim”.

”And when you ask people for money they give money,” he said.

Mam, who is probably 43 but does not know her exact year of birth, declines to speak publicly about Ning and did not respond to an interview request from Fairfax Media.

Legros, a French aid worker who speaks fluent Khmer, married Somaly when he was 20 and they lived together for 13 years, co-founding in 1996 a non-government-organisation called Afesip, a French acronym for Acting for Women in Distressing Situations.

Legros left Afesip in 2004, three years before the creation of the New York-based Somaly Mam Foundation to be Afesip’s global fund-raising arm.

He said he was ”mostly pushed out” of the organisation because Mam wanted it to be a solely Cambodian-run operation, but at the time he was not happy with the way it was being managed.

”I told her I don’t want to be part of your life or your organisation any more,” Legros said he told Mam. ”I was basically left on the street with two suitcases. I lost everything.”

With three centres in Cambodia, Afesip’s staff of more than 100 work to free trafficked victims, bring perpetrators to justice, and rehabilitate victims through mental healing, vocational training, improved literacy and core life skills.

In October, Estee Lauder announced the opening of a Somaly Mam beauty salon in Siem Reap, close to the famous Angkor Wat temple complex. Sex-trafficked victims will be trained there.

However, Afesip’s stand that all sex workers are victims is divisive among sex worker activists, and some Cambodian sex workers shun the organisation.

Sou Sotheavy, a 75-year-old transgender former sex worker, said Afesip works too closely with police, who have been accused by rights groups of widespread abuses against sex workers during sweeping raid-and-rescue operations against brothels.

”Closing brothels looks like the right thing to do for sex workers, but it actually pushes them back into more dangerous situations on the streets,” she said.

Afesip has been accused of accepting sex workers picked up in police raids, which Human Rights Watch said constitutes ”arbitrary arrests and detention of innocent people”.

Former sex worker Srey Mao, 31, twice escaped from Afesip after being taken there by police. She said she was not happy at the centre because they were teaching her sewing, a skill she thought would not help her care for her one-year-old son.

”I didn’t have my freedom,” Mao said in between collecting paper scraps on Phnom Penh’s streets, which she sells for less than $1 a day. ”I don’t want to go back to the centre.”

Some non-government-organizations in Cambodia criticize Afesip for using sex abuse victims to tell their stories to raise money.

On November 9, the luxury US travel company OmLuxe is taking 20 people paying more than $2000 each to Cambodia, where they have been promised they will be able to spend time with sex-trafficking victims.

Australian volunteer Toni Palombi, who worked in Afesip in 2006, said she resigned because she disagreed with the organization’s approach to assisting women. ”I found it to be dis-empowering and, in fact, harmful in some instances,” she said in a report for external evaluators written after she left.

”Additionally I was very concerned with the lack of freedom bestowed to women in the organization’s shelters and with the lack of procedures in place to deal with serious issues in the event of abuse or harassment.”

Palombi, whose post was funded by the Australian government, said a strategy to bring journalists and filmmakers to the organization’s Kampong Cham centre put children at risk of exploitation.

She said the organization was at the time in a financial crisis and was ”not considering the quality of its services but rather was desperately trying to find funds”.

Responding to questions from Fairfax Media, Somaly Mam’s communication department said the organization has worked with thousands of survivors who have been cared for in shelters, each with a story to tell.

”It is their truths that help the world to better understand the deep, dark realities of human trafficking and sexual exploitation,” the department said.

It hit out at people challenging the stories of victims.

”Those women who choose to publicly share their personal stories about sex trafficking are courageous and strong and we are saddened when forces work to silence their voices and seek to distract from building awareness of this critical global problem,” it said.

Pierre Legros said that despite a bitter divorce from Mam he is proud of what she has achieved both inside Cambodia, where she is so powerful she can pick up the phone to call the Prime Minister, and outside the country, where she has been feted by the world’s royalty, megastars and top business people, raising money for Cambodian sex victims.

”She is beautiful, intelligent, charming and manipulative … she is the perfect person to lead the organisation,” he said.

Asked about Mam’s personal story, Legros said he had no doubt she was abused when she was young. ”She was a prostitute. Was she abused? Yes. Was she trafficked? I doubt it. No one has proof,” he said.