The first cases of HIV identified anywhere in the world are widely thought to have been in Los Angeles in 1981. Since then, 45,000 Angelenos have contracted HIV and nearly half have died due to the disease.

As terrible as that statistic is, we can look back over the last 30 years with considerable pride because Los Angeles’ courageous response to the epidemic also saved many lives. We now know how much worse things would have been had local elected leaders not braved controversy to support one of the most effective HIV prevention tools we have: needle exchange.

How much worse? Consider some comparative data — needle exchange isn’t solely responsible for the differences in these statistics, but it plays an important role.

In 1992 in Los Angeles, where needle exchanges were already in effect, the rate of HIV among those who injected drugs was 8.4%. In 1993, the HIV rate in Miami for that population was the highest in the country: 48%. Although Miami put into place HIV-prevention programs, there has never been a large-scale needle exchange program there. Today the rate of HIV among injection drug users in Miami is 16%. In Los Angeles, the rate stayed low, and as of 2009, the most recent data available, it was 5%.

These facts have important consequences. Extrapolating from county data, it’s believed that about 34,000 Los Angeles residents are injection drug users. The California Department of Public Health calculates the lifetime costs of treating one person with HIV at $385,200. If those 34,000 Angelenos had an HIV rate of 16% rather than 5%, we’d be spending an additional $1.4 billion in treatment costs.

People affected by HIV/AIDS in the late 1980s and early 1990s faced all kinds of discrimination. Our civic leaders displayed wisdom and guts with a series of early actions in response to the epidemic, beginning with the country’s first AIDS anti-discrimination law in 1985.

Four years later, L.A. put in place an AIDS coordinator, Fred Eggan, who provided a structure for the city to partner with community organizations to raise public awareness, prevent new HIV infections and support those affected by HIV/AIDS.

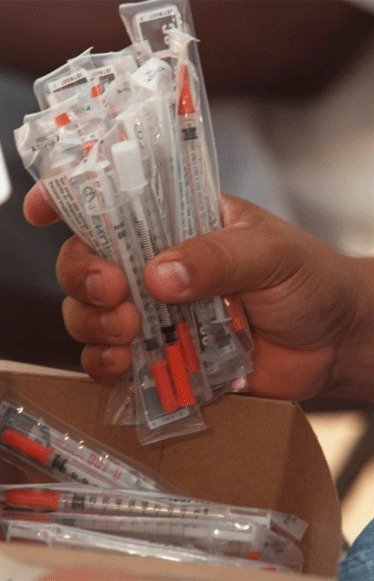

Needle exchange came next. It was highly controversial at first. Activists and volunteers, including the founder of my program, Renee Edgington, began the exchange underground in the late 1980s; it was formally established in 1992. They faced protesters, prosecution, conflicts with private security, law enforcement, even citizen’s arrest.

Critics objected: Why give people who inject drugs the tools they need to break the law? It seemed to many observers that swapping sterile needles for used needles would only make things worse. But city leaders held firm, and decades of research have now vindicated decisions by the city and later county leaders who bet on needle exchange. In fact, more than 200 studies from the U.S. and abroad agree: Needle exchange programs not only prevent HIV, but people who use them are also more likely to enter drug treatment and get off drugs.

People who inject drugs will keep doing it with or without access to clean needles. Reusing old syringes greatly increases the risk of staph infection or the antibiotic resistant MRSA; sharing syringes leads to HIV and hepatitis C infection.

Ask anyone who’s ever injected drugs how difficult it is to get sterile syringes without exchange. In California, some pharmacies sell syringes without a prescription, but they are few and far between. Most don’t offer disposal or referrals to badly needed wraparound and referral services such as medical care and access to drug treatment. Outside of

the participating pharmacies and needle exchange programs, there are few options other than buying them on the street.

Earlier this year, Stephen Simon, the city’s fifth AIDS coordinator, left the job for the private sector. Stephen was a tenacious champion of the city’s exchange programs and syringe access in California.

“It’s been a tough political challenge,” Simon told the City Council as he left, but “we removed more than a million dirty needles from the streets of Los Angeles each year…. That’s the kind of tough political decisions that you all have made here.” Council members Bill Rosendahl, Eric Garcetti, Tom LaBonge, Paul Koretz, Dennis Zine and Ed Reyes all spoke with gratitude of Simon’s tenacity and creativity in guiding the city’s fight to reduce HIV and AIDS.

So far, however, Simon’s job hasn’t been filled. And yet the HIV epidemic is still with us, and we still need city and county help to protect the progress we’ve made so far. We still need local government to stand up against continuing and misguided opposition to needle exchange.

In a time of polarized political conversation and a distressed economy, it may be tough to remember how important L.A.’s pioneering prevention strategy has been. We can’t afford to throw away people, or money, on treating those whose illnesses we could prevent. Not in times like these. L.A. needs to keep supporting needle exchange programs, and it needs to advocate for and coordinate with those programs.

Shoshanna Scholar has served as the executive director of Clean Needles Now/Harm Reduction Central in Los Angeles since 2003.

LA Times