Sex workers’ rights are workers’ rights and human rights — because sex workers are human beings doing work. That’s why the debate over sex work shouldn’t focus, as it usually does, on whether sex workers are “criminals” or “victims.” Instead, sex workers themselves should have agency and a say in the policies that govern their practices.

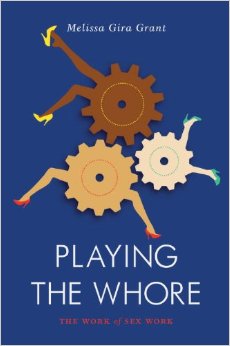

It’s surprising how controversial those statements are, but they are missing from virtually every discussion of sex work in the United States. The ideas do, however, form the core of Playing the Whore, a fascinating new book on the state of the sex work debates by Melissa Gira Grant. Grant is one of the most interesting policy thinkers in the country when it comes to sex work, and this short book introduces and outlines her thinking on the matter.

The book covers everything from the historical origins of terms like “red-light district” and “prostitution” to the intense intra-feminist debates about sex work as a feminist issue. But since Wonkblog is a policy blog, let’s look at the policy arguments on sex work. There are three big takeaways:

1) If your proposal for what to do about sex work involves “more policing,” you are likely heading in the wrong direction.

The recent wave of activism by sex workers started with demands for scaled-back police involvement. The group COYOTE was founded in 1973 to oppose criminalization. Then, in 1975, 100 sex workers took over a church in Lyon, France, to protest arrests by police.

Making sex work illegal doesn’t mean the practice goes away. It just means that the police become the de facto regulators. And often that sort of regulation can have harmful consequences.

For example: Many cities have passed ordinances saying that carrying condoms counts as evidence that a person is “loitering for prostitution.” These laws often make sex workers less likely to carry condoms at all. In the end, laws that are intended to protect women and public health turn out to make things worse. (Indeed, Human Rights Watch argues that the HIV/AIDS death rate in New Orleans is twice as high as in the rest country, in part because of these laws.)

More generally, sex workers usually can’t go to the police with problems and expect a response. Instead, they have to worry about being threatened with arrest. The power differential here has historically led to many cases of abuse. Sex workers identifying themselves in public to seek redress — a fundamental part of any type of activism or democratic accountability — puts them at risk.